CWD spreads where state wildlife governance fails and captive deer industries face little oversight.

Image courtesy of Rocky Ridge Whitetails, Pennsylvania.

Chronic Wasting Disease Is Spreading Because State Wildlife Governance Is Failing

How Weak Oversight and Industry Pressure Are Driving the CWD Crisis

Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) is an always-fatal neurological disease that threatens the future of wild deer across North America.

Its spread is not inevitable: it accelerates when state wildlife systems fail. In many states, rules governing captive deer and elk movement, testing, and reporting lag far behind what science tells us is necessary to protect wildlife that should be held in the public trust.

In Texas, that systemic vulnerability collided with something worse: a private deer-breeding industry that treats wildlife like inventory, combined with loopholes and weak enforcement that make it easy to hide violations. Recently, a prominent breeder allegedly falsified records, dodged disease-testing rules, and moved deer under the table … and now multiple animals tied to the “ghost deer” investigation have tested positive for CWD.

What is Chronic Wasting Disease?

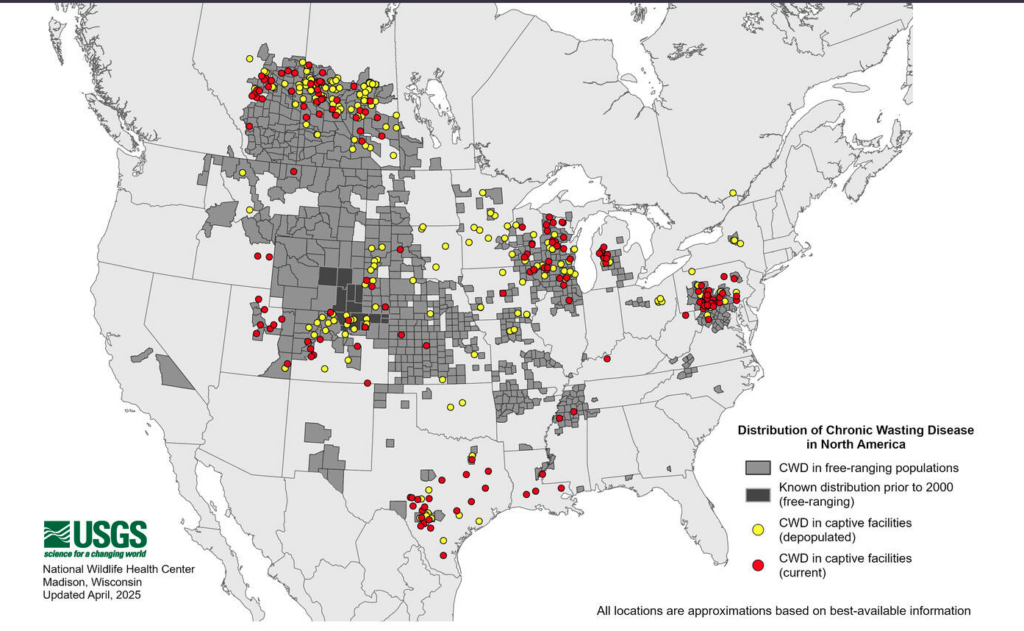

First identified in Colorado in the late 1960s, CWD has since spread to many U.S. states and several other countries — a warning sign of what happens when a persistent wildlife disease meets fragmented oversight and high-risk industry practices.

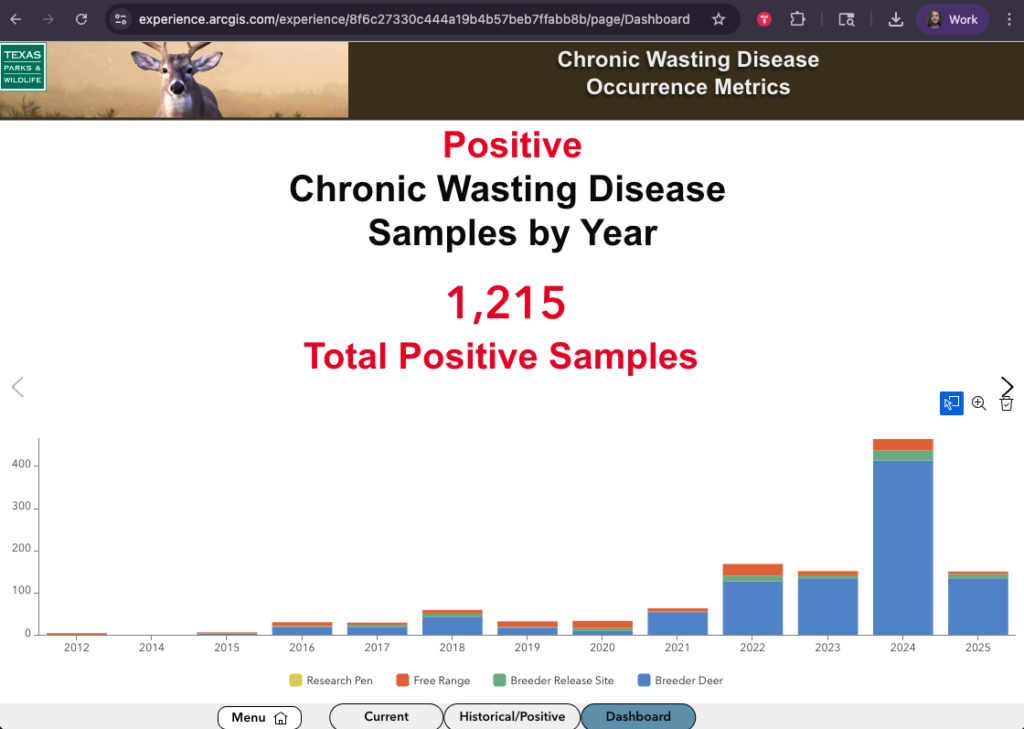

CWD has been present in Texas for more than a decade. The first known case was recorded in 2012 in a wild mule deer in the Hueco Mountains of West Texas. Just three years later, the disease was detected in a white-tailed deer inside a deer breeding facility in Medina County, west of San Antonio.

Since then, the pattern has been unmistakable: 87% of all CWD cases in Texas have occurred in captive breeding facilities, not in free-ranging herds.

CWD spreads easily through saliva, urine, feces, blood, and contaminated environments. Infected deer gradually lose neurological function, experiencing severe weight loss, lack of coordination, drooling, and drooping ears — symptoms that often go unnoticed until shortly before death.

As one expert put it bluntly, “This disease is literally eating holes in the deer’s brain.” The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says CWD has not been shown to infect humans, but it strongly advises people not to eat meat from infected animals.

Because the disease is 100% fatal, it is one of the largest threats facing deer and other cervids today.

Conservationists have repeatedly warned that allowing deer from breeding facilities to mingle—directly or indirectly—with wild deer is one of the most significant drivers of CWD spread. Yet instead of tightening safeguards, wildlife agencies face relentless political pressure from breeders and ranchers to weaken testing requirements and lift quarantines that limit the sale and movement of captive deer. That pressure has real consequences for wildlife held in trust for the public.

Wait, you can farm deer?

Image courtesy of Orion Whitetails, Wisconsin.

CWD didn’t spread because deer are “the problem.” It spread because we’ve allowed a little-regulated industry to commercialize wildlife, and because state laws across the country have created loopholes big enough to drive a deer trailer through.

Across the U.S., the captive deer industry has exploded. Across the U.S., captive deer breeding and shooting preserves operate in a patchwork of legal definitions and weak safeguards.

A 2016 Wildlife Society survey found:

- 20 of 32 states had deer-breeding facilities — anywhere from 5 to 1,332 sites — holding more than 140,000 captive deer.

- 20 of 29 states had commercial shooting preserves holding another 25,000+ deer.

- These facilities weren’t even regulated consistently: captive deer were considered wildlife in some states, livestock in others, and game animals in a few — making enforcement wildly uneven.

- Only a minority of states required basic safeguards like minimum acreage, release times before deer can be shot, stocking density limits, or habitat standards.

This legal gray zone created perfect conditions for disease to spread: high densities of stressed animals, long-distance transport across state lines, inconsistent testing, and minimal public oversight — even though the consequences fall squarely on the public’s wildlife.

That’s why CWD didn’t emerge from nowhere. It emerged from a system that treated deer like inventory rather than public trust resources.

And the Texas “ghost deer” case is just one example of what can go wrong. In that case, a prominent breeder allegedly falsified records, moved animals through a black-market network, and evaded testing requirements. Multiple animals tied to the operation later tested positive for CWD.

This legal gray zone also enables a lucrative industry built on transporting deer across state lines, selective breeding for grotesquely oversized antlers, and selling semen, urine, and trophy animals like commodities. The economic incentives are enormous: an estimated 10,000 deer and elk farms in North America generate more than $4 billion a year, and the push for profit drives movement of animals and lobbying for weaker rules.

And while industry leaders deny problems, the reality is simple: moving captive animals around the country increases the risk of moving infected animals, period. Wildlife biologists and many hunters have been sounding the alarm for years. CWD thrives in exactly these conditions: high densities, long-distance transport, inconsistent testing, and escapes from captive pens that allow for mingling with wild animals.

And weakened state oversight makes the issue worse. In Missouri, for example, fewer than half of breeders participated in voluntary disease monitoring, and Idaho only requires CWD testing of farmed elk for 10% of carcasses which the producers can select.

While scientists haven’t been able to prove a direct causal link, the circumstantial evidence is alarming. In Missouri, all wild deer that tested positive for CWD were found within a 29-square-mile radius of two infected captive facilities. Wildlife agencies in numerous states have documented wild positives appearing near farms previously thought to be disease-free.

Image courtesy of Missouri Farm Bureau.

How does this epidemic of CWD keep spreading?

This isn’t an isolated scandal. It’s a symptom of a governance model that allows political pressure, industry interests, and decades-old policies to override public trust and science-based safeguards.

State wildlife agencies are not just failing to contain CWD — they are allowing a major source of contamination to continue operating for private profit. When a commercial industry moves live wildlife, biological materials, and contaminated animals across the landscape, the costs of disease fall on wild deer, ecosystems, hunters, and the public at large.

That raises a fundamental question under the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation that these agencies purport to follow: how does allowing wildlife to be commercialized, transported, and exposed to disease for private gain align with the principle that wildlife is a public trust resource?

Can carnivores control CWD?

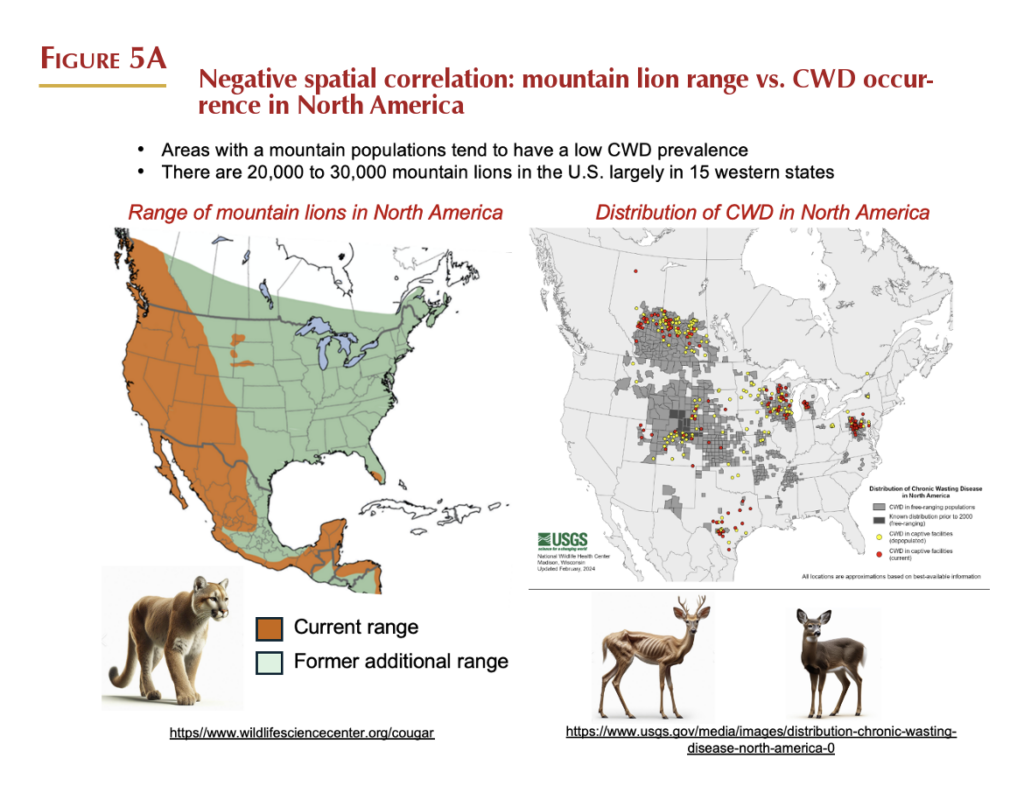

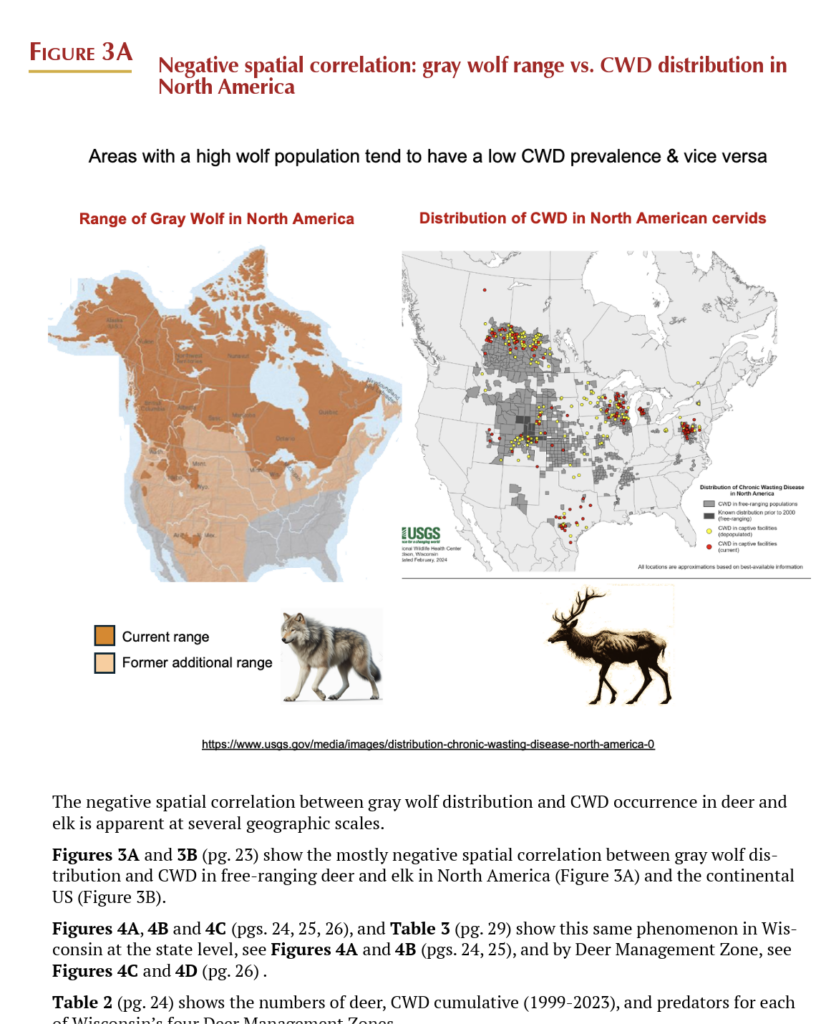

At the same time, state wildlife management continues to suppress one of nature’s most effective disease-response mechanisms. Carnivores can detect and selectively remove sick animals year-round using their superior senses, such as an olfactory capacity in wolves that is estimated to be 10,000 times more powerful than that of humans. While no one claims predators can eliminate CWD entirely, a growing body of ecological evidence suggests they can slow its spread and reduce its prevalence in infected herds.

Emerging research suggests that large carnivores don’t just remove sick animals, they may also significantly reduce the amount of infectious prions entering the environment. A 2023 study examining bobcats fed CWD-infected material found that only about 2% of prions remained detectable in scat after one day, roughly 1% the next day, and none by the third day.

These findings mirror earlier results from studies of mountain lions, indicating that most ingested prions are neutralized or sequestered during digestion rather than reintroduced into soil and plants where they can remain infectious for years.

In a 2021 experiment, captive mountain lions were fed mule deer tissue spiked with CWD prions. Researchers recovered only 2.8–3.9% of the original prion load after gut passage, and prions were shed only during the first defecation following consumption. The majority of ingested prions were effectively eliminated, suggesting that mountain lions feeding on infected carcasses may reduce environmental contamination.

Long-term exposure studies are even more striking. Over nearly 18 years, captive mountain lions consumed parts of more than 432 CWD-infected deer carcasses — representing over 14,000 kilograms of infected material — without showing any clinical signs of prion disease. Extensive tissue testing revealed no evidence of CWD infection, findings that align with broader research showing strong barriers to prion transmission outside the deer family. In short: predators can safely consume infected prey without becoming disease reservoirs.

Similar results have been documented in other carnivores. In a separate study, captive coyotes removed most CWD prion infectivity from elk brain tissue during digestion, with prions no longer detectable one to three days after ingestion.

Together, these findings point to an overlooked ecological reality: intact ecosystems with functioning carnivore communities may help limit the environmental persistence of CWD.

It’s also important to be precise about what we know, and what has yet to be studied. There are currently no published studies directly measuring how wolves process or shed CWD prions after consuming infected animals. However, observational patterns across North America are telling. To date, CWD has generally failed to establish or persist in areas with intact, active wolf populations, instead appearing along the margins of wolf territories or in regions where wolves have been heavily reduced or eliminated.

This does not prove that wolves prevent CWD. But combined with what we know about predator selectivity, carcass removal, and prion reduction in other large carnivores, including other canids like coyotes, it raises a critical question for wildlife governance: why are states aggressively suppressing wolves and other carnivores while simultaneously claiming they lack tools to slow the spread of wildlife disease? Ignoring ecological function while accommodating high-risk commercial practices is not “science-based management,” it’s political expediency.

As veterinarian Jim Keen, D.V.M. documented, and wildlife biologist and former Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation CEO Dr. Gary Wolfe have argued, it is ecologically irresponsible not to consider the role of predators in managing wildlife disease. Wolves function as “CWD border guards,” Gary Wolfe says, naturally culling infirm animals before they shed prions into the environment.

Yet many states aggressively reduce wolf populations through extended hunting and trapping seasons, undermining a natural check on disease while simultaneously permitting high-risk captive wildlife operations to continue largely unchecked.

Ignoring this body of evidence while weakening predator protections and accommodating high-risk captive wildlife industries isn’t just inconsistent, reveals the priorities of a wildlife governance system that caves to political pressure instead of defending ecological function and public trust.

This isn’t a Texas problem, or a Missouri problem, or an Idaho problem. It’s a national, structural failure that state wildlife agencies and lawmakers are failing to contain.

The Texas “ghost deer” case is just one visible example of what happens when oversight collapses: wild deer suffer, ecosystems are destabilized, and the public is left to deal with the consequences.