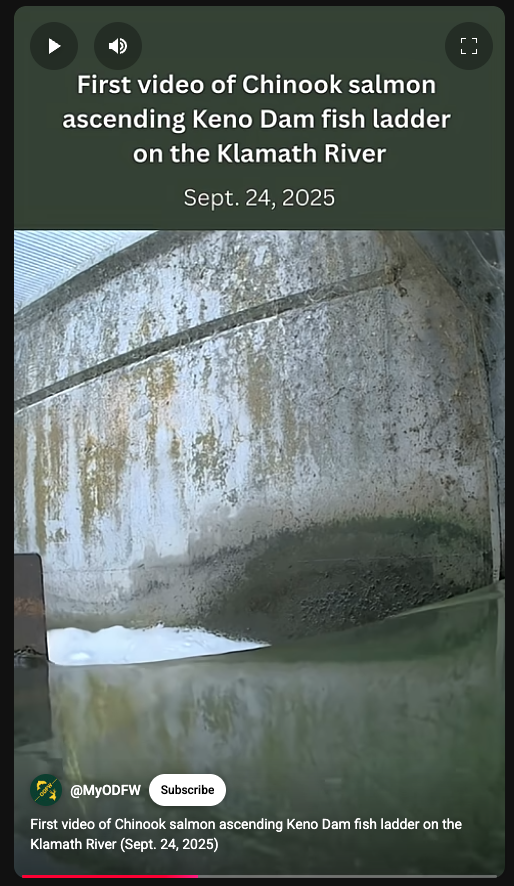

Watch: Chinook salmon returning to the Klamath River in this video from ODFW.

Salmon Returning to Klamath River’s Upper Reaches for the First Time in a Century

For the first time in more than a hundred years, a Chinook salmon has been filmed leaping past Keno Dam on Oregon’s upper Klamath River. The video, captured September 24 by a monitoring camera installed only the day before, shows the fish clearing the final pool of the fish ladder—a single flash of silver that carries generations of history.

For the first time in more than a hundred years, a Chinook salmon has been filmed leaping past Keno Dam on Oregon’s upper Klamath River. The video, captured September 24 by a monitoring camera installed only the day before, shows the fish clearing the final pool of the fish ladder—a single flash of silver that carries generations of history.

This lone salmon is more than a remarkable sight. It’s proof that a river can heal when we remove the barriers. Just one year after four massive hydroelectric dams came down on the Klamath—the largest dam-removal and river-restoration project in the world—salmon are again reaching habitat long denied to them.

A Historic Homecoming

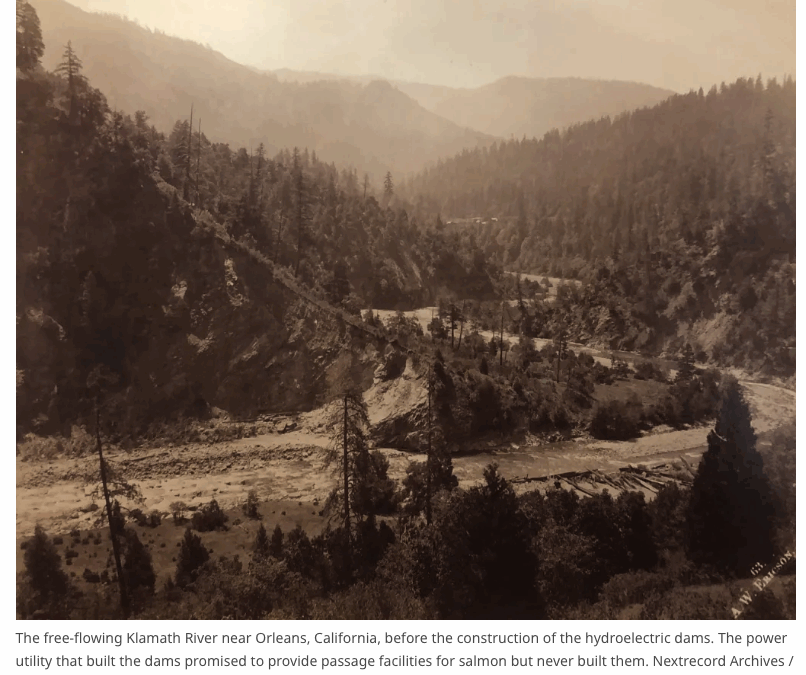

The Klamath once hosted one of the West Coast’s greatest salmon runs, feeding Indigenous nations and nourishing entire ecosystems. But early-20th-century dams blocked more than 400 miles of spawning grounds, collapsing fish populations and depriving Tribes of a central food source and cultural touchstone. Salmon are keystone species: their annual migrations carry ocean nutrients deep into mountain watersheds, feeding everything from bears and eagles to riparian forests themselves. When the fish disappeared, entire food webs suffered.

The sight of a single fish may seem small, but it signals something profound. Salmon have not had access to these upstream waters since the early 1900s, when a series of hydroelectric dams—J.C. Boyle, Copco No. 1, Copco No. 2, and Iron Gate—cut off more than 400 miles of their historic spawning habitat. Those dams ignored the treaty rights of the Yurok, Karuk, and Klamath Tribes, whose cultures and diets depended on abundant salmon. The removal of the dams is not only an ecological triumph; it is also a partial restoration of those long-violated rights.

Last year, the J.C. Boyle, Copco No. 1, Copco No. 2, and Iron Gate dams were finally removed after decades of organizing led by the Yurok, Karuk, and Klamath Tribes and their allies. The four massive dams, ranging from 33 to 172 feet tall, were dismantled over the past year in the largest dam removal project in U.S. history. Crews executed a controlled drawdown of the reservoirs to prevent downstream flooding, managed decades of accumulated sediment, and began large-scale revegetation efforts. Already, native willows and sedges are sprouting in the former reservoir beds, early signs of a river reclaiming its banks.

The tribes’ victory restored the river’s natural flow and reopened ancient migration corridors. Tribal leaders describe the removal as an act of justice as much as ecology—repairing a wound that state and federal policies inflicted for more than a century.

Now, a single Chinook clearing Keno Dam signals the next chapter. Most of the best spawning habitat lies upstream of Keno and Link River dams and Upper Klamath Lake. For salmon to return here so soon is a testament to their resilience—and to the persistence of the people who fought for this river.

Challenges Await Salmon Returning to the Klamath River

The journey isn’t over. Salmon still must navigate Link River Dam, cross Upper Klamath Lake’s sometimes-poor water quality, and find cool, clean tributaries for spawning. Irrigation diversions, unscreened canals, and climate-driven drought add to the obstacles. The lake poses challenges of its own: recurring toxic algae blooms, fueled in part by agricultural runoff, can degrade water quality and threaten fish health.

State and federal agencies, Tribes, and conservation groups continue to monitor the run and restore habitat throughout the watershed, as well as water quality, so these first pioneers will not be the last. The Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, in partnership with the tribes, is already expanding habitat surveys and considering new fish-passage solutions at the remaining barriers.

Climate change adds another layer of complexity. Warming river temperatures, reduced snowpack, and unpredictable precipitation patterns are shifting migration timing and stressing cold-water species like salmon. Their resilience—returning so quickly once the barriers were removed—underscores both the urgency of climate adaptation and the importance of free-flowing rivers.

Despite these hurdles, the first Chinook at Keno renews hope. Last year, more than 500 adult fall-run Chinook successfully spawned below the former dam sites—the first confirmed reproduction in Oregon’s portion of the Klamath Basin in over a century.

A Lesson for the West

The Klamath River restoration proves that bold action works. For a century, Western water policy favored cheap power and irrigation over living rivers and Indigenous rights. The removal of these four dams shows another way: we can right historic wrongs, revive fisheries, and safeguard biodiversity in an era of climate stress.

Other watersheds are watching closely. From the Snake River in Washington to the Eel River in California, communities are weighing whether to remove aging dams that no longer justify their ecological costs. The Klamath River’s rebirth shows what’s possible when communities confront hard truths about water management, honor Indigenous leadership, and commit to bold restoration.

A flash of silver in a fish ladder might seem small. But as that single salmon pushes past the last pools of a long-blocked ladder, it carries with it a promise: rivers can heal, and with them, the cultures and species that depend on their flow.