The R3 Effect: How Pittman-Robertson Funding is Being Redirected from Wildlife

From Conservation to R3: How Pittman-Robertson Funds are Diverted from Wildlife Protection

When you hear “wildlife restoration,” what comes to mind? Protecting forests, rivers, and habitats? Funding research on declining species? Unfortunately, federal programs designed for that purpose are increasingly being diverted.

One key program is the Pittman-Robertson Wildlife Restoration Act, passed in 1937. Often called the P-R Act, it was designed to channel excise taxes from firearms, ammunition, and archery equipment into state-level conservation projects. Its goal was straightforward: those who use wildlife for recreation—hunters and shooters—would help fund habitat restoration, species research, wildlife monitoring, and public access to wild places. In short, the Act was intended to transform taxes from users into real, science-based conservation.

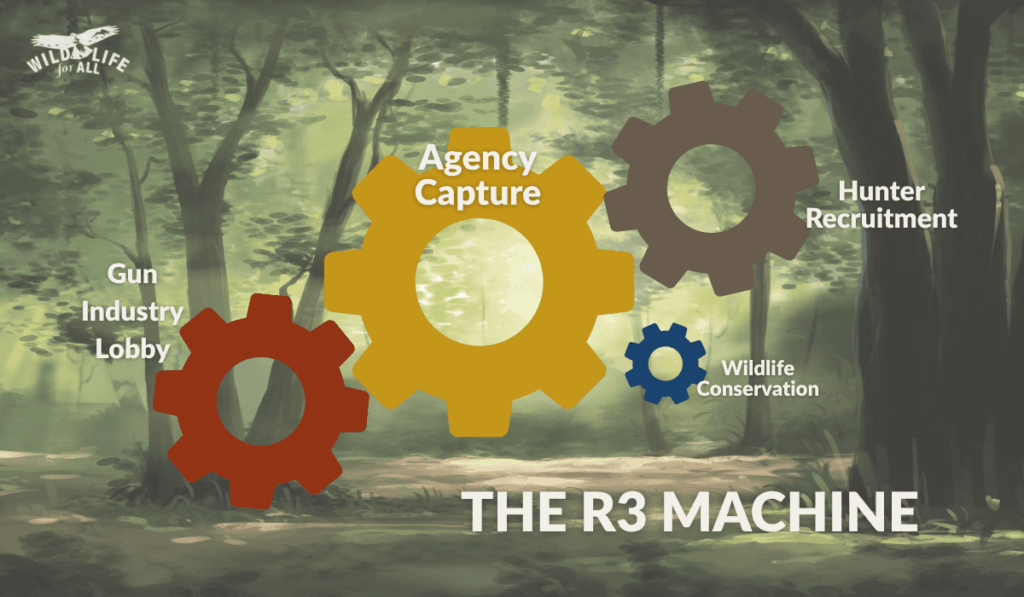

Over time, however, changes to the Act and pressure from the hunting and gun lobbies have allowed state agencies to redirect these funds. Today, a growing share of P-R dollars goes to programs aimed at recruiting, retaining, and reactivating hunters—the so-called “R3” initiatives—rather than to the conservation work the Act originally intended.

Because let’s be honest: when you picture wildlife conservation work, you probably don’t imagine 3D archery tournaments or the construction of new shooting ranges. But this is shockingly where some federal conservation funding is being spent.

In Oregon, for example, the Department of Fish and Wildlife hosted a $10 “family friendly” 3D archery event with 40 animal-shaped targets scattered along a two-mile trail in recent months. In Louisiana, the state wildlife agency is using P-R dollars to fund shooting range development for public, private, and even commercial entities.

In Oregon, for example, the Department of Fish and Wildlife hosted a $10 “family friendly” 3D archery event with 40 animal-shaped targets scattered along a two-mile trail in recent months. In Louisiana, the state wildlife agency is using P-R dollars to fund shooting range development for public, private, and even commercial entities.

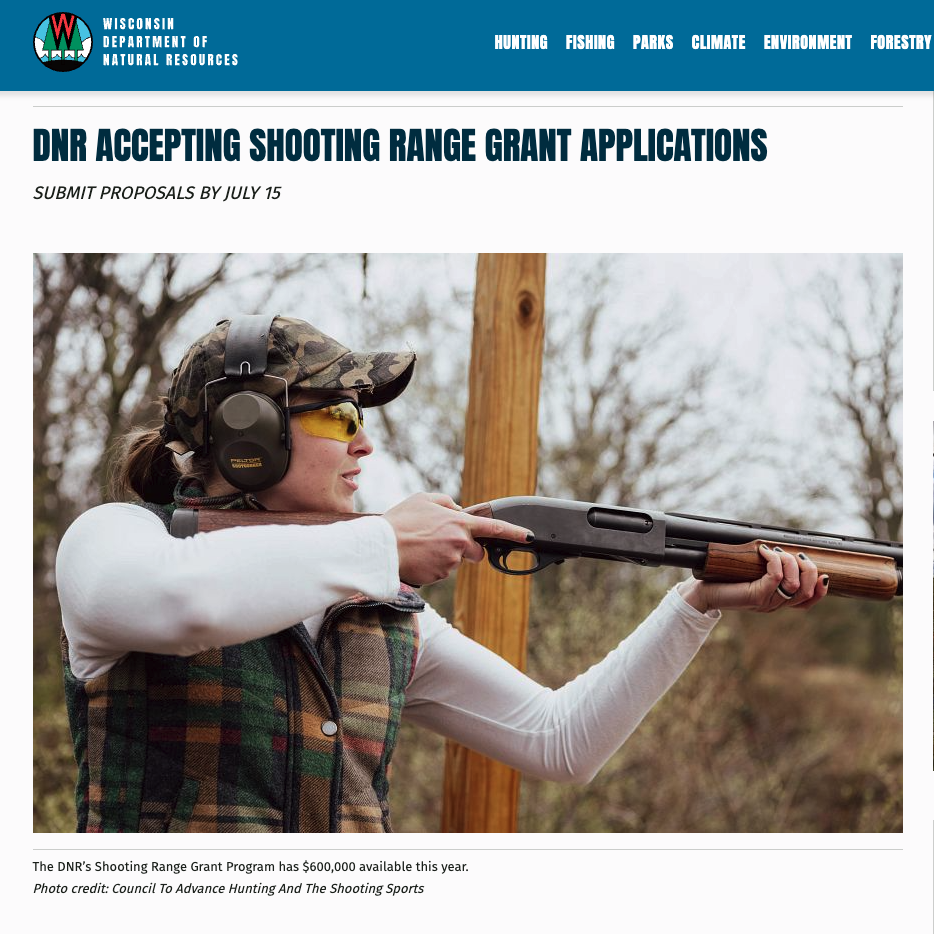

And in Wisconsin, the DNR is recently offered $600,000 in grants for shooting range upgrades or new construction using P-R funds. Past projects have included shooting benches, restrooms, indoor ranges, and backstop renovations—with a clear focus on “near highly populated areas” to attract more participants to the shooting sports.

These activities aren’t random, and they happen all over the country. They’re part of a growing push known as “R3”: Recruit, Retain, and Reactivate—a coordinated campaign to reverse the long-declining trend in hunter participation by diverting conservation funding toward promoting hunting and shooting sports.

In short, during a global extinction crisis requiring an all-hands-on-deck effort to conserve and protect declining species, state agencies are instead abusing the nation’s largest pot of restoration funding to promote recreational gun use and other “shooting sports.”

Who benefits? Not wildlife, but the National Rifle Association and the trophy hunting lobby.

What Was Pittman-Robertson Meant For?

Enacted in 1937, the Pittman-Robertson Act was designed to funnel excise taxes from firearms, ammunition, and archery equipment into true conservation projects—things like habitat protection, species research, wildlife population monitoring, and public access to wild areas. In theory, it was an elegant model: users pay, wildlife benefits.

Over time, however, budget pressures and organized lobbying by hunting industry groups and the gun lobby pushed state agencies to redirect those funds. In 2019, Congress passed the “Modernizing Pittman-Robertson Act,” allowing these dollars to be used more broadly on R3 initiatives—shifting the emphasis from conservation to hunter and gun marketing.

It’s important to note that while it’s often believed that hunters are the primary contributors, approximately 73% of P-R funds are generated by non-hunters. This includes individuals who purchase firearms and ammunition for purposes such as sport shooting, personal defense, or law enforcement, rather than hunting. This broad base of contributors underscores the public’s investment in wildlife conservation, not just those who hunt.

However, despite this widespread support, the allocation of P-R funds has increasingly favored programs aimed at promoting hunting and shooting sports, rather than direct conservation efforts. This shift raises concerns about the equitable distribution of resources and the alignment of funding with the original intent of the P-R Act.

Two key funding streams now support R3-style activities through the USFWS Hunter Education program: the Basic Hunter Education and Safety Program and the Enhanced Hunter Education and Safety Grants Program.

Basic Program: Funded by half of the excise taxes on pistols, revolvers, and archery equipment, this program apportioned an average of $136 million annually between FY2015–FY2019. These funds are used not only for hunter safety programs but also for building and operating public shooting ranges.

Enhanced Program: This program receives a statutorily fixed $8 million per year. If a state has used up its Basic Program funding, it can use Enhanced Program funds for broader purposes—including hunter development, shooting ranges, and even public relations efforts to promote hunting.

While these programs represent a minority share of total Pittman-Robertson apportionments, they are growing—and they symbolize a shift in purpose from conservation to gun user recruitment. What’s more, the “modernization” of P-R made it easier for states to justify using broader Wildlife Restoration funds for R3 initiatives.

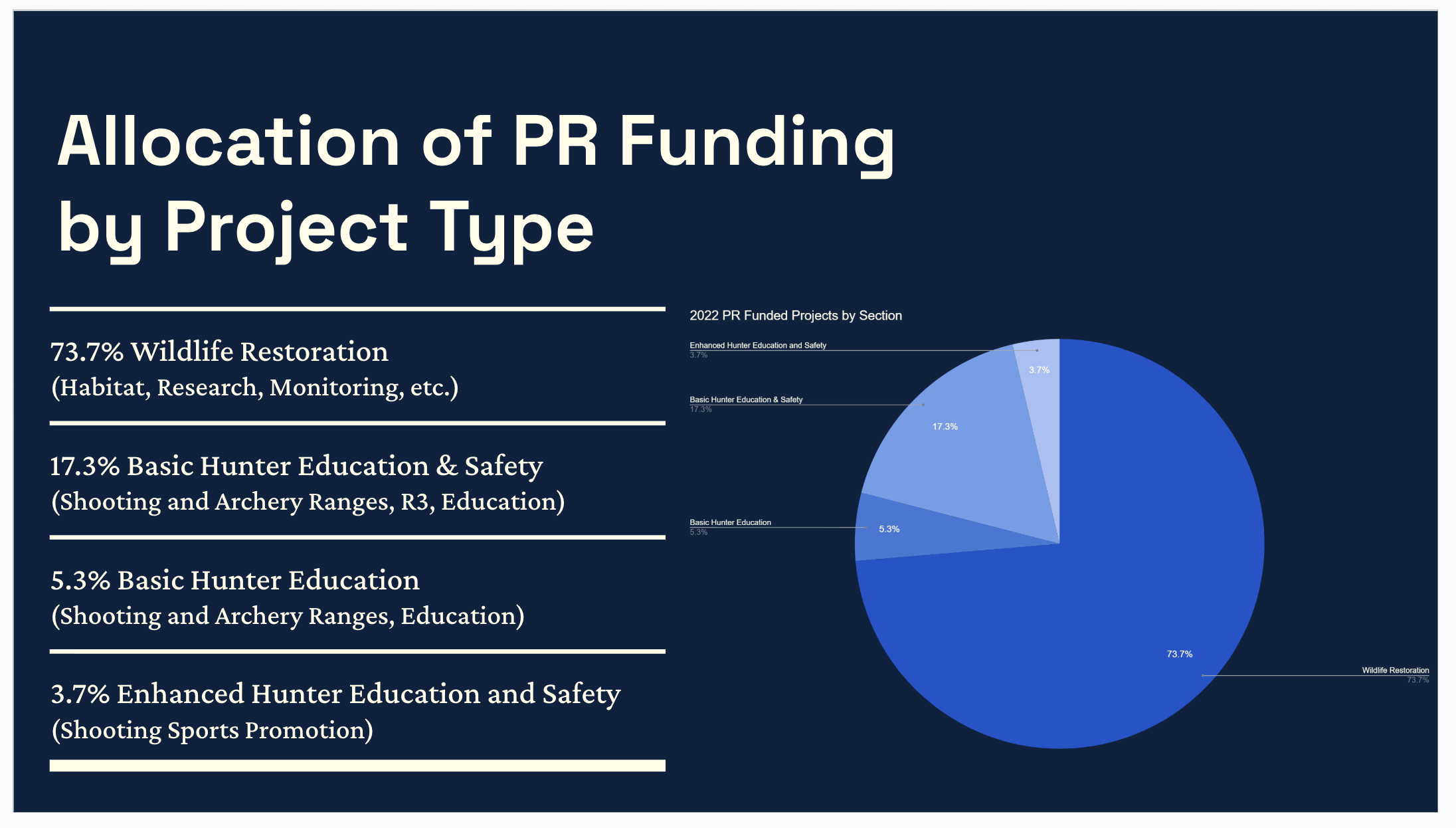

According to new analysis by our research intern Sophia Bremer, MS:

- In FY2024, P-R allocated just under $1 billion in total funds to state agencies.

- Across more 1,800 FY 2022 state projects she reviewed:

- 73% of funds went toward wildlife restoration and management.

- 17.3% went to seasonal or mobile shooting ranges, R3 programs, and intermediate hunter education.

- 5.3% funded permanent shooting and archery ranges and beginner hunter education training.

- 3.7% supported shooting sports promotions like youth hunting camps and marksmanship contests, as well as updating existing facilities.

While most dollars still go toward wildlife restoration on paper, the trendline is clear: the emphasis on R3 is growing, especially in how agencies justify and structure their budgets.

Graph courtesy of research by Sophia Bremer, MS

What’s the Problem?

Biologists—trained in ecosystem science and habitat management—are being pulled away from actual conservation work to become marketers for hunting. Agencies are spending limited funds trying to sell the public on hunting rather than investing in actual science-based conservation. At the same time, the public they’re targeting is more interested in “shooting” wildlife with a camera, not a gun, and those wildlife are declining due to overexploitation, habitat loss and the other causes of the sixth mass extinction being orchestrated by humans.

Let’s be clear: archery shoots and shooting ranges are not conservation. They are recreation and little evidence exists to support that they somehow translate to conservation. And building public relations campaigns to convince people to take up hunting again does little to help the 80% of U.S. species that are declining in abundance or at risk of extinction.

Let’s be clear: archery shoots and shooting ranges are not conservation. They are recreation and little evidence exists to support that they somehow translate to conservation. And building public relations campaigns to convince people to take up hunting again does little to help the 80% of U.S. species that are declining in abundance or at risk of extinction.

Even worse, P-R now actively excludes any organization that might question or critique hunting or trapping practices. By law, P-R funds cannot be used for programs that “promote or encourage opposition to regulated hunting or trapping.” This silences science- and ethics-based perspectives that challenge the dominance of lethal wildlife management—even when those critiques are grounded in ecological research. And it means groups pushing for more ethical, ecologically grounded wildlife conservation are locked out of federal funding—no matter how sound their science may be.

Perhaps more interestingly, a 2022 study by the Wildlife Management Institute (WMI) offers a revealing look into the effectiveness of state-level R3 programs aimed at bolstering hunting and fishing participation. While these initiatives are designed to attract new participants, the study indicates that they predominantly engage individuals who are already active or previously involved in these activities.

Specifically, a significant portion of R3 event attendees had purchased licenses in the year prior to participation, suggesting that these programs are more successful at simply engaging existing enthusiasts rather than the purported goal of introducing new demographics to hunting and fishing.

Moreover, the study highlights that R3 events centered around advanced techniques or specialized equipment are not effective in increasing participation and engagement. Notably, youth under 18 exhibited the lowest increase in participation and engagement. These findings suggest that current R3 strategies are not effectively reaching or resonating with younger audiences or those without prior exposure to hunting and fishing, which begs the question, “so what are these tax dollars paying for?”

A Broken Incentive Structure

The funding model itself creates perverse incentives. Through the complicated P-R funding algorithm, state agencies receive more of the money when they sell more hunting licenses, which warps agencies into hunter-serving bureaucracies, not conservation institutions accountable to diverse public constituencies.

The NRA and the trophy‑hunting lobby turn these federally matched Pittman‑Roberts dollars into a steady source of revenue for lobbying and targeted marketing to boost gun sales. For example, one study revealed that a substantial share of state‑matching funds has been earmarked for projects that expand trophy‑hunting opportunities and firearms retail.

This warped incentive structure is so perverse that agencies stoop as low as blatant tokenism of women and BIPOC communities in their R3 programs. Instead of addressing the inequalities leading to the nature gap—the current reality that people of color suffer from a lack of access to nature due to racial and economic disparities—state wildlife agencies use minorities in their marketing campaigns but do nothing to make access more affordable or safe for those same people. Similarly, pink hunting gear is an insulting and vacuous way to recruit women into an activity many are simply not interested in.

It’s not that hunters are the problem. Many hunters care deeply about wildlife and authentic conservation. The problem is a governance system that puts the interests of a shrinking minority above the needs of the broader public and the ecosystems themselves.

And ironically, while hunter numbers have dropped steadily for decades, P-R revenues have increased—because the vast majority of excise tax funds now come from non-hunters purchasing firearms and ammunition. As stated above, 73% of taxable items that generate these funds are bought by non-hunters—purchases for law enforcement, sport shooting, personal defense, or other reasons. Yet those funds still go into a system dominated by hunting interests.

What We Should Be Funding Instead

If we want to stabilize wildlife populations and preserve ecosystems, we need to refocus conservation funding on conservation itself. That means:

- Funding science-based recovery plans for declining and threatened species.

- Restoring degraded habitats and corridors.

- Monitoring biodiversity and ecosystem health.

- Supporting coexistence strategies for carnivores and communities.

- Elevating non-consumptive uses of wildlife and public lands.

- Encouraging the next generation of conservationists by providing safe, affordable access to wild places.

Instead of funnelling money into P-R campaigns for hunting, let’s invest in what biologists do best—protecting and conserving wildlife for everyone.

The Pittman-Robertson Act has played a critical role in American conservation history but its original purpose has been distorted. It’s time to reimagine how we fund and structure wildlife governance in the 21st century—one where wildlife conservation reflects ecosystem needs, scientific integrity, and the broad public interest.

R3 may win short-term gains for participation numbers, but it’s a losing game for long-term conservation. We need to shift back to a model where the health of wildlife and people—not the health of hunting license sales—is the central goal.

We must push for reform that returns this funding to its core mission: wildlife conservation grounded in science, ethics, and the public trust.

It’s time to stop marketing shooting sports as if they help wildlife. Let’s actually restore habitat, fight biodiversity loss, and provide our rapidly dwindling wildlife with the protection they need.